When it comes to medical advances, few inventions have revolutionized the industry more than the hypodermic needle and syringe. Since their invention in 1844 by Scottish physician Alexander Wood, the development of these tools has enabled much safer and more efficient procedures to be performed on patients. This article examines the early development of the hypodermic needle and syringe, focusing on its evolution from large-gauge needles that caused pain and infection to today’s 34G hypodermic needles for superficial epidermal punctures that are virtually painless and minimally invasive.

History of hypodermic needles and syringes

The first documented use of a hypodermic needle was in 1853 when French surgeon Charles Pravaz used a hollow metal tube with a small sharpened point at one end to inject morphine into his patient’s arm. While this was the first recorded use of what is now known as a hypodermic syringe, it wasn’t until later that year that Boston physician Francis Rynd used a similar device with an even finer tip that could penetrate deeper into muscle tissue. From here, numerous improvements were made over time, culminating in the invention of the glass syringe in 1889 by the German physician Theodor Curt Schleich.

Development of the 34G hypodermic needle

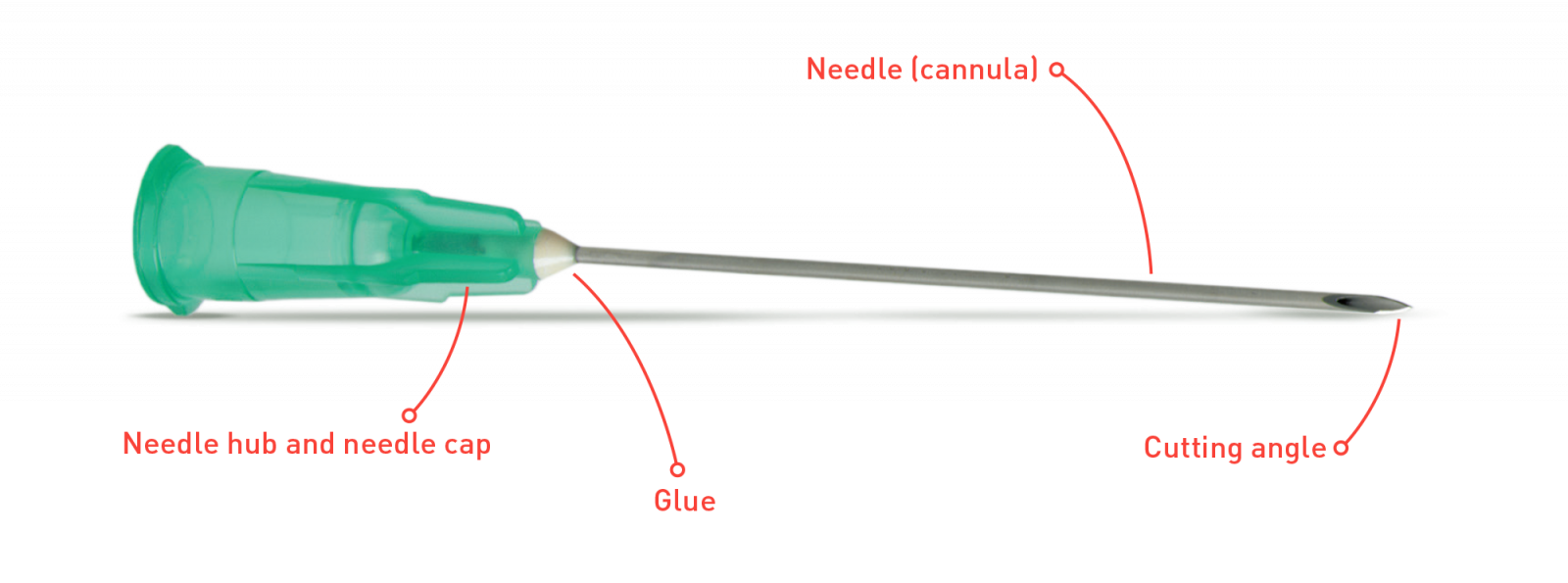

In recent years, advances have been made in designing and constructing hypodermic needles, resulting in thinner-walled needles capable of injecting medication into smaller areas such as subcutaneous fat or superficial layers of the epidermis. One such innovation is the development of 34G hypodermic needles specifically designed for superficial epidermal punctures due to their ultra-thin walls. These types of needles are now widely used by healthcare professionals around the world and provide a much safer method than traditional larger gauge needles of delivering medication directly under the skin without causing damage or discomfort.

Advantages of 34G hypodermic needles

34G hypodermic needles offer many advantages over other types, including increased precision, less pain during injection, and reduced risk of infection from contaminated surfaces due to their tiny size and narrow tip design. In addition, these types of needles can also help prevent accidental drug overdoses as they allow precise dosing without wasting medication, which can often occur with larger gauge needles due to their wider hips and higher dosage capacities. Finally, these thin-walled devices require less force to insert, making them ideal for delicate procedures such as intradermal injections or intramuscular vaccinations where accuracy is paramount.

Safety considerations when using 34G hypodermic needles

While there are many benefits associated with the use of 34G hypoemdric needles, some safety considerations must be taken into account before using them in medical practice. As mentioned above, these devices have extremely fine tips that can easily break if mishandled, so the proper technique must be used when inserting them into patients’ skin or muscle tissue; otherwise, serious injury may result from accidental injection or laceration caused by improper handling techniques. In addition, special care must be taken to ensure that these types of devices are not reused on multiple patients, as this could lead to cross-contamination between individuals, thereby increasing the risk of infection or disease transmission between them.

Conclusion

The advent of 34G hypodermic needles has revolutionized the medical industry, giving healthcare providers access to highly accurate instruments capable of safely administering drugs under the skin without causing unnecessary discomfort or damage, while reducing the risks associated with accidental overdose or contamination through re-use between patients. It’s largely thanks to this advancement that we’ve seen significant improvements across all areas of medicine, enabling doctors to treat their patients better and faster than ever before.